PART TWELVE: March 1985 – February 1988

LIFE ON THE FRONT LINE

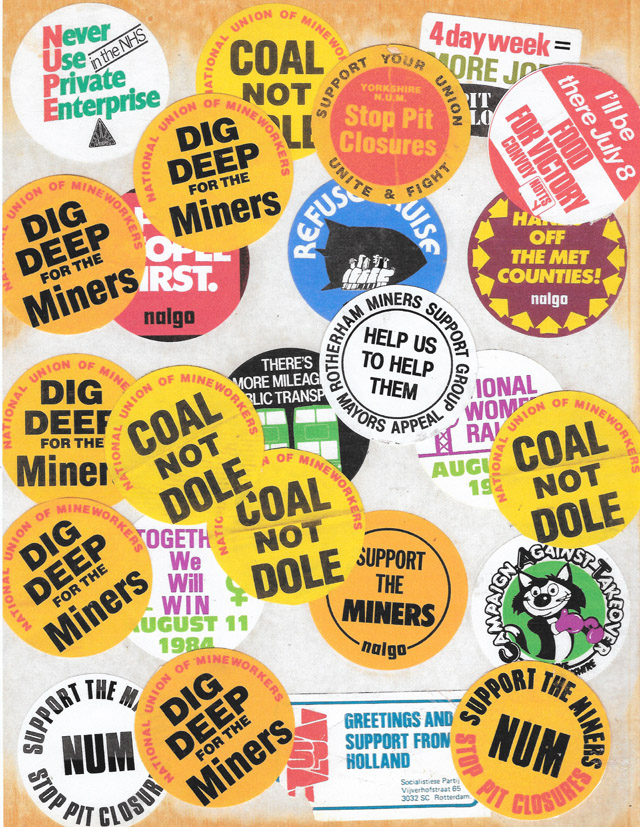

In the 1984-85 Miners’ Strike

Bruce Wilson

PART TWELVE: March 1985 – February 1988

The march back to work, scabs, redundancy and the last shift.

‘LET’S GO BACK WITH OUR HEADS HELD HIGH’

I was sat watching television Sunday evening and a ‘news flash’ came on. The miners’ strike was over. Well, I don’t know what to say, that came out of the blue. I told the wife, the news flash did not last long, it just left me wondering, “just like that, it’s over.” Nobody even asked us what we thought. I want to carry on. I have no intention of surrendering. I got in the car, picked the lads up and went to the Baggin’. No picketing from now on. Looks like the strike is over. There is a big meeting at the Baggin’ Silverwood Miners’ Welfare tomorrow.

Monday, 4th March 1985.

Picked lads up and went to the big meeting at the Baggin’ a lot of sad faces today. It’s all happened so quick, not much talking going off between the men. You could see the look of disappointment on some men’s faces. I’m still in shock. Me and the lads want to carry on, as do a lot of others. But the simple fact is, more miners have gone back to work. About 86% of Yorkshire are still out.

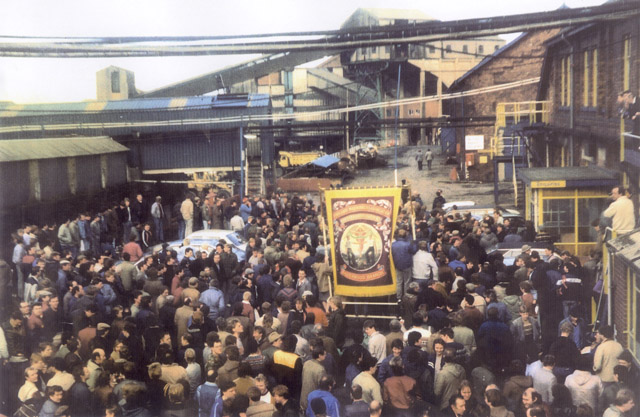

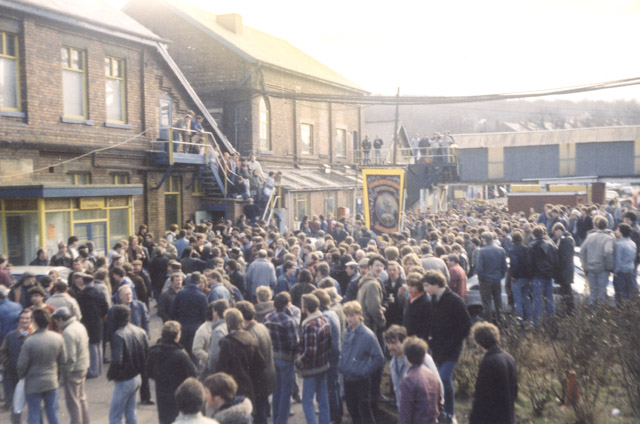

Our Union men got on the stage and spoke, outlining the fact that we had to go back to work. ‘SO LET’S GO BACK WITH OUR HEADS HELD HIGH’. The march back to work will commence at 8.00am tomorrow from the Baggin’ [Silverwood Miners Welfare]. We will walk to the pit behind our banner.

Tuesday, 5th March 1985.

I picked the lads up and arrived at the Baggin’ at 7.45am. No Captain Bob this morning, he’s gone on the march back to work at his own pit, Cortonwood, the ‘Alamo’. I almost forgot Captain Bob was not a Silverwood lad, he has been with us for that long.

The march started at 8.00am. Hundreds of miners, their wives and supporters marched behind the banner. I held back, I stayed back, I did not want to go back. But I followed the pit banner, walking up the hill to Thrybergh. Then following the road to Silverwood. On the march I was not upset, just annoyed and bitter; and also had a feeling of being let down. Not by the NUM, but by the scabs and people – people in their comfortable jobs in other industries. Mind you, it could be their turn next.

We did not go back to work today there was a picket line on, I was told they were sacked Kent miners and Armthorpe men. We refused to cross their picket line. Our Silverwood NUM official asked for the picket to be removed so he could talk to the pit manager about the Silverwood miners who had been sacked during the dispute. We just went into the pit yard with our banner, completing our ‘march back to work’.

In the pit yard we noticed a couple of scabs a few hundred yards away watching us. They were stood near the coal preparation plant, a member of management and the personnel manager went dashing off in their direction and told them (scabs) to get out of sight. After the closure of Cortonwood, Captain Bob Taylor was transferred to Silverwood. He would say it was like ‘coming home’. Well he did know everybody, and everyone knew Captain Bob.

Wednesday, 6th March 1985.

I was due to start back work on afternoons, at 12.00. That morning I had to attend the Rotherham Magistrates Court for non -payment of fines. Got there early but all the aisles were full of people. I had a word with the court usher, telling him that it was my first day back at work and I did not want to be late, so he got me in first.

The court room was full and I was called to stand in front of the magistrate. He asked me why I had not paid my fines and what my intentions were to pay. There I was, stood with a bread bag in my hand which had my snap in for work. I explained to the magistrate that this was my first day back at the pit, after 12 months on strike, I had no money and a young family. I offered to pay my fines off at a pound a week. The magistrate accepted my offer, as I turned round to walk away, he called my name, I looked round and he said ‘Good luck’. Immediately a lump came to my throat. It was as if he recognised what we had done. I just could not say anything, just nodded in acknowledgement. I felt very proud.

I got to Silverwood with minutes to spare, I did not want the sack for being late on my first shift back. Got my checks from the deployment, then I ran into the pit baths to get changed. I got undressed, put a towel round me, and went into the ‘mucky side’ Bloody hell!, I spent ten minutes whacking my pit clothes into shape, they were rock hard, and my socks!, if I’d have whistled them, they would have followed me. They had not been worn in 12 months, stiff as two cricket bats.

I met up with my mate Shaun [Bisby] our first day back at Silverwood was spent wandering round the pit top. We sat in the blacksmith’s cabin, the fitter’s cabin, moving around all the time, we got bored to tears. For the rest of the week we reported to Silverwood on the afters shift, we just wandered around the pit top. Only a few men went underground on the first shift. According to Dave Vickers [pit bottom loco driver] a big clean- up had taken place before the men had returned to work. The pithead baths and certain places on the pit top were ‘disgusting’. The previous tenants left discarded food and rubbish all over the place, and there was excrement in the showers.

One of the lamproom attendants returned to work to find a load of oil lamps missing and some panes of glass broke in the lamproom windows. What caught his attention was that the shards of glass were on the floor outside the lamproom. You don’t have to be Sherlock Holmes to work that one out. The same happened at Kilnhurst Colliery on their return to work (Derek Feltham, a lamproom attendant at Kilnhurst found the same).

For several days we reported to Silverwood on ‘Afters’ and continued our wanders around the pit top. After this they sent us in buses to Thurcroft Colliery where we went underground. Me and Shaun just sat in the roadways, away from anybody and no one bothered us. An undermanager walked by us, bent down (the roadways were not very high) and just said, “morning, you lads from Silverwood?” We just nodded. He never bothered us.

We did not like going to Thurcroft, we wanted to get back to our own pit. Back working at Silverwood, I was put back on the locomotive. I don’t think any of the men knew what to say or think. No one talked about the previous twelve months. It was as if we had just been on a two-week holiday and were having ‘Monday morning blues’.

On a few occasions when I went into the pit bottom for supplies an undermanager would come past me, leading a line of scabs. I looked the other way. He looked like Snow White leading the seven dwarfs. He would shout out to his followers, ‘NOW THEN SCABBIES, COME ON AND FOLLOW ME’ and they would disappear down 18’s empty road, to the shaft sump, which was a horrible, damp place, water dripping on you from half a mile above- then stay there for seven hours. Some of the scabs (you knew them) would sometimes look at you and smile. I would look the other way. One day one of the scabs shouted my name, ‘Bruce!’ (he was a locomotive driver like me before the strike), I ignored him, got on my locomotive and drove off. What a lovely life and existence they had now. When the undermanager called them ‘COME ON MY SCABBIES’ we would have got the sack for that. I don’t feel sorry for them but I wonder what they would do if they could turn the clock back.

Friday, 15th March 1985.

I drove my car into Thompson’s Scrapyard at Parkgate. I have been having problems with it. I’m working now but still can’t afford the repairs. It weighed in for twenty pounds. I have to pay the Council for every bit of coke we had from them. We have no fuel. Still waiting for a delivery.

Yesterday, underground, I took a big risk. I got a big brown paper sack and a pick, then I set about getting a bit of coal from the Barnsley seam in the old workings. One lump fell from the coal seam as soon as I hit it with my pick, being exposed, and all the weight on it made it ‘easy to get’. At the end of my shift, riding the shaft I looked nine months pregnant, the lump of coal was hidden under my coat. If caught, it would probably be instant dismissal. I have two little kids at home.

I saw our local policeman the other day. The last time I saw him was face-to-face on the picket line at Orgreave. He was ok. As I walked up and down the police front line you could tell by the look on his face and his nervous acknowledgement of me that he did not want to be there.

SCABS, REDUNDANCY AND THE LAST SHIFT.

It was not long before the management exerted their rights to ‘manage’ and the principles of Thatcher appeared loud and clear for all of us to see. I got the impression our union was totally ignored. At the top end some managers started throwing their weight around. I got a note on my pit checks at the start of my shift. Mr. Wilson – from the Personnel Manager. You have been repeatedly warned about leaving your place of work early, your pit bonus for the week has been stopped. ‘I don’t think so!’

I went straight to see the personnel manager, ‘I’m not standing for this’ I politely put my case across, disputed my note and won my case. I’m sure this was an exercise to show who was the boss. No discussion, just orders. There were instances at Silverwood where management tried to victimize and sack men who had been active in the strike. One day a union man went out of the mine, it was, by all accounts the management’s intention to sack him. All the men underground, sat silent by their machines, waiting for the management’s next move. Wisely the miner was not sacked, this happened a few times. Silverwood men still had some fight in them.

When you saw Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (under manager and scabs) they never ventured far from the pit bottom and they were treated like lepers, just ignored, although a few of them did try to gain acceptance. Some scabs-well, you did not really hate them, but just thought that they were funny and not realised what they were doing. In one instance a scab ‘management’ who we had to work under daily came into the underground locomotive garage on the day shift, he never carried a water bottle, he would pick up anyone’s and take a swig. A loco driver knew this and urinated in his water bottle and left it on a bench. As sure as night follows day the scab ‘management’ came into the garage, picked up the water bottle and drank from it ‘this waters warm’ he said, then someone told him what he had drank. Anyone else would have gone out of the mine feeling poorly, he took it. Another time his snap tin was nailed to a bench. He took every insult in the book and never reported us- that’s how much he wanted to be accepted. But they never were.

One day I came face to face, alone with a scab in the Medical Centre. I had something in my eye and had to go out of the mine. When I entered the Medical Centre, ‘I could have died’ I came face to face with a scab. I thought I would just have to be polite and get on with it. The scab said to me ‘what’s the matter Bruce? My eye I replied, there’s something in it. Sit down I will be back in two minutes. When he came back, there was only me and him in the Medical Centre, he smiled and told me to open my mouth wide and shut my eyes, I did as instructed, but I opened my eyes and watched him pretending to undo his flies. Well I had to laugh, I’d fallen for it ‘pit humour’. I came across one scab many times after work. He would just say ‘Hey up!’ not a care in the world. Well as I’ve said, some of them did not know any better. I did acknowledge some of the management, they were not worth getting the sack for but they were kept at arm’s length.

In the summer of 1985 things settled down and got back to ‘normal’ although nobody ever mentioned the strike which I thought strange. It was though men had blanked twelve months of their life off, or just been away for a week’s holiday. Our old district opened up, me and Shaun got back to loco driving, taking men and supplies down Braithwell No3 trolley road. Development men were driving a roadway into new coal reserves off an old roadway that ran for three miles.

As time moved on I ‘wanted out’. All the men I knew and worked with from before the strike were leaving left, right and centre. Redundancy was offered to men in their late fifties, no one was left at the pit over 55 years old. Then it got to 50. On some days certain jobs could not be manned up, the shortage of manpower was so bad.

In the summer of 1987 I put my name down for redundancy and my mate Shaun did the same. I used to look at the list of names of the men that were ‘going’, every Monday morning. When I used to get my checks at the start of the shift I would ask in Deployment, “any letter for me?”

Then about the middle of November, Shaun, lucky bugger, got his redundancy notice; to finish that week, with twelve week’s pay up front, about fifteen hundred pounds. I carried on working without my mate Shaun, I had to wait until the end of February 1988 for my escape letter. I used to count the weeks and days to go. The personnel manager called me into his office, Monday morning at the end of the day shift and told me the news, also said that I must work the rest of the week and not to let him down. I agreed and as I turned round he said, ‘I expect a drink from you!

On my last shift, Friday morning. 6.00 am. Underground, I took the men in as usual, talked to the lads who I had worked with over the years. They were sorry to see me go and I said I would miss them. At the end of my shift I took the manager out on the mail, he was my guard. Reaching the out-bye mail station, I switched the loco off, leaving it for the afternoon shift. The manager walked off. I followed him, looked behind me, down the roadway for the last time, gazing at the roadway’s and the old districts. I knew I would never work down there again. Made my way to the pit bottom, no rush, taking in all my surroundings and thinking about the many happy memories-our carefree, pre-strike days over.

Near the pit bottom was a stainless steel plaque, about twelve inches long and twelve inches wide, commemorating the Queen’s visit to Silverwood in 1975. One or two men had their eyes on that plaque. Men still talked about that royal visit when they whitewashed all the coal seams on her underground route. She rode the swallowood mail, to the end, and rode back, everything whitewashed.

I rode the shaft for the last time, on my own. I went into the pithead baths, got showered and changed. Then I kept a promise I had made to the personnel manager. I walked across the road to his office with the cheapest bottle of wine I could buy, knocked on his door, walked in and said ‘that drink I promised you Mr Harrison’, I put it on his desk, turned round, said ‘goodbye’ and left. The look on his face, I don’t know whether it was a look of disgust or surprise! My days as a miner were over.

YORKSHIRE NUM, NO SURRENDER.

FOR THE STRIKING MINERS’ OF 1984-85.

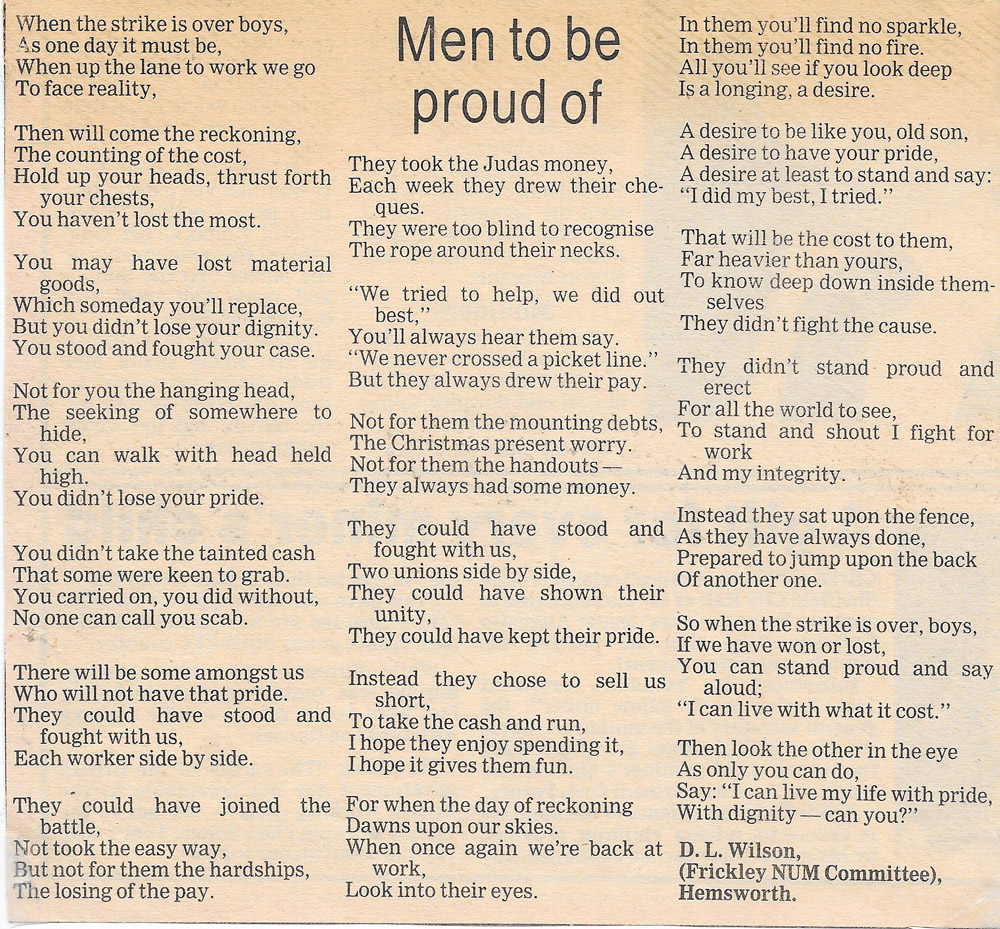

To think and to do are two different things. Actions speak louder than words. In 1984 the miners’ did it without any questions asked. They fought for their beliefs. They can look anyone in the eye and hold their heads high. They set an example that others may follow. What more can any man ask.

Follow

Follow