Last days as a steelworker, early days as a miner

In the steelworks nobody bothered you as long as you did your job. Radio’s in cabins, card schools everywhere. It was like one big holiday camp at times. After handling hot metal you would get a ‘beer note’ which allowed you to go to the pub for half an hour. This was one of the perks of the job that was constantly abused. The half hour turned into a full session in the pub sometimes.

I was just a young man and didn’t have a care in the world. One day in the summer of 1975. I took a mate to the Great Yorkshire Show at Harrogate in North Yorkshire. I should have been on the afternoon shift. Starting at 1pm. Driving home after dropping my mate off, I came to a ‘T’ junction at a main road, there was a police roadblock, they stopped me, and wouldn’t allow me to continue my journey home. I had to wait until ‘The Queen’ went past.

Two hours I waited. When I got to work at Rotherham it was 3pm, my shift manager wanted my explanation for been late, I told him in all honesty. It was the Queen, she made me late. He couldn’t argue with that.

Then one Friday night on the night shift I went to the pub, my mate was supposed to clock me in, only he didn’t turn up for work that night, and when I turned up at 1am, the shift manager was waiting for me. I deserved all I got, I was “too familiar with the job”. I got the sack.

I was ready for a change though, it was practically impossible to get the sack at that time in the steelworks. The management gave me plenty of warnings. I went to sign on at the dole office, this was in October 1977. At that time you got ‘make up money’ equivalent to your weekly wages. After several months it got less and less.

In January 1978 the local jobcentre were advertising for trainee miners. I applied and was accepted subject to a medical. I got my date for a medical in early January at Manvers main training centre.

Arriving at the medical centre I sat in a little dark room waiting to be called in by the Doctor. After sat in the waiting room for ten minutes the doctor called me into his ‘surgery’, and told me to drop my trousers and cough. He then checked me over, did more tests, that was about it, I passed, no hernia and a clean bill of health.

Not long after I signed up and started my training at Manvers Main Colliery in the old Silkstone seam. One of the things we had to do was push a mine tub full of muck right up to a conveyor belt. The tub wheels locked into a device that held it firm, then you pulled a lever and the mine tub tipped up, tipping its contents onto the conveyor belt. After doing this a few times and shovelling up the muck that formed a heap on the floor the training officer told us that what we were doing were out of date practices and we would never have to do them again.

Then another time we had to get one end of a fire hose and run up the underground roadway pulling it out as if rushing to a fire. Well I was getting paid for all this. Another day we had self-rescuer training, this was the ‘stainless steel box’ that you carried on your person when you went underground, (it went onto your belt along with your cap lamp battery) it was for carbon monoxide, you snapped the seal on it and it broke in two, you then pulled the mask out, put it on your face and breathed. It gave you valuable time underground to reach oxygen and safety in the event of a fire. The exercise for this was. Several tables lined up in a room to represent a low roadway, then you got on your hands and knees and crawled about underneath the tables for several minutes and ‘not take your mask off’.

Every pit had its ‘own ghost’ and Manvers Main was no exception. Sat having our snap underground we were told about ‘La loo’ the Manvers pit ghost and strange happenings underground.

After a few weeks of training I was sent to Silverwood Colliery near Rotherham a fully-fledged Miner. I started on CPS (Close Personnel Supervision) and worked with Albert and Tom, two old hands on the 9-5 shift, we went checking conveyor belts and greasing them.

I used to tell them where I’d worked and my experiences in the steelworks, it frightened them to death. I couldn’t understand why. Albert and Tom had their snap in old roadways, sat in the dust, muck and the noise of a conveyor belt clanging in your earhole. I used to make my way to the pit bottom, ride the shaft out of the pit and go to the canteen for my breakfast. ‘I wasn’t sitting in a mucky unlit roadway for my snap’. I did this for a couple of days.

Then one day a man with a stick pulled me up in the pit bottom, the Colliery Overman! He asked me, “where tha’ gooing lad?”

“For my breakfast” I replied.

The Overman said to me “every time that chair goes up that shaft it costs the Coal Board hundreds of pounds and tha’ gooin art for thi’ breakfast! Don’t do it no more, na’ get back on thi’ job”.

I found it hard to get used to at first, everything was so regimental, men following you about with sticks telling you what to do. After this I never went out of the pit again for my breakfast. Later I went to work with the stone dust team erecting a shelf high up in the roadway arches and putting a layer of stone dust on them, near the coalfaces and developments. If there was an explosion, the force of the blast would blow the stone dust all over like a dust cloud, hopefully dampening the explosion.

Another Customary procedure that you had to get used to was washing each other’s backs in the shower. I had only been working at Silverwood Colliery for a week, coming out of the mine at the end of my shift in my ‘Pit Muck’ I went to the mucky side of the pit baths got stripped off, wrapped a towel round my waist and entered the shower.

I was just about to start washing myself down with my soap and sponge when this bloody great miner came up to me and said ‘can I wash thi’ back lad’, all this was strange to me, but I had heard about this custom. Well this bleeding great miner put his sponge on my back, pinning me to the shower wall and started rubbing up and down, I ended up going up and down the wall with his sponge, I’m only 10 stone wet through. Then he turned round showing me his back and told me it was his turn to have his back done. Well I managed to wash his back, it was like wallpapering our front room wall he was that big! I always took note of who was in the showers after that and kept out of his way.

After a working a few at months at Silverwood Colliery, I left and in April 1978 me and my mate Mark Lloyd decided to go and work away, down south at Torquay in Devon. We went into the training office and saw Ronnie Muir and Jeff White, they both tried to talk us out of it, but we packed in and went to work at Torquay.

I got a job at Pontin’s holiday camp in Paignton as a waiter. It was wonderful for a while, I was thinking there more to life than the pit, I met my future wife down there, Gay. She worked in the cigarette and paper kiosk.

After the season ended I went back home to South Yorkshire. I looked for work in the local Jobcentre but there wasn’t a deal, the Jobcentre staff noticed I had been a miner and pointed out to me that Silverwood Colliery were setting supply lads on. I agreed to apply, the Jobcentre phoned the pit up and arranged an interview for me. I was a trained miner and they were crying out for trained men the Jobcentre staff told me.

I went to Silverwood pit training office, I met Ronnie Muir and Jeff White again, after no more than ten minutes they gave me a job, but they had to clear it with Mr Cyril Critchlow the personnel manager. Ronnie phoned Mr Critchlow, the look on Ronnie’s face told it all, Mr Critchlow says you can’t have a job because of your previous bad timekeeping, well I didn’t take kindly to that, because it wasn’t true, I never had days off.

I thanked Ronnie and Jeff for their time and I told them I was going to see Mr Critchlow. I didn’t want that on my work record, ‘bad timekeeper’ so I went over to his office and knocked on his door, he called me in. I introduced myself. I said to him ‘no job fair enough’ but it’s not true about my timekeeping, he looked at me, paused for a minute then said you start on the Monday afternoon shift on 9’s loader gate supplies; go and get kitted out, get your new pit checks made and a pit lamp allocated. We got on well after that, I stood no crap off him and visa-versa.

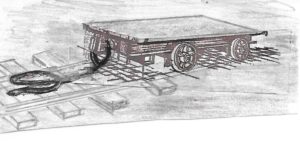

Well my first job back down the pit was ‘tramming’. A new roadway, No 9’s district in the Swallowood Seam, no electric, no power no nothing on it. The roadway was several hundreds of yards long and pitch black, no lighting. The floor was lifting in places, very uneven, any supplies that were needed in the driveage heading had to be taken up manually. I had to load a ‘skelly’ a flat mine car with steel arch rings, corrugated sheets, bags of cement, pit props, or any manner of things, then I threw a rope over my shoulder that was attached to the mine car coupling ‘and pull’, you had to do this continuously all shift, red hot, sweating like a good un’ but I enjoyed every minute of it.

This was 1978. In 1979 a year later, I was sat in the locomotive garage on the night shift, I was an underground loco driver now. Someone rang up from the pit top to inform us Maggie Thatcher had won the election. One of the older miners said, ‘you had better get ready; that woman Thatcher has won the election’. In the next few months things changed drastically, jobs were harder and harder to come by, the pits books suddenly closed. Once jobs in mining and steel were easy to get, where sons and daughters of miners and steelworkers could expect to follow their mothers and fathers into jobs like generations before them had come to an end.

Follow

Follow