Thatcher had secret plan to use army at height of miners’ strike

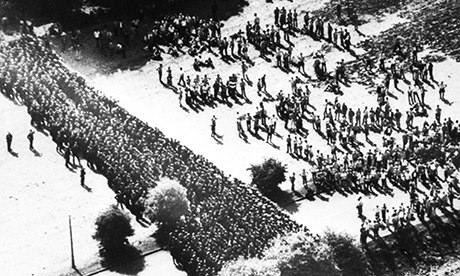

Ranks of police face the picket line at Orgreave Coking Plant near Rotherham in June 1984. Photograph: Pa/PA Archive/Press Association

Ranks of police face the picket line at Orgreave Coking Plant near Rotherham in June 1984. Photograph: Pa/PA Archive/Press Association

Margaret Thatcher was secretly preparing to use troops and declare a state of emergency at the height of the miners’ strike – out of fear Britain was going to run out of food and grind to a halt, government papers released today reveal.

The 1984 cabinet papers, released to the National Archives, show that Thatcher asked for contingency plans to be drawn up to use troops to move coal stocks, despite official government policy ruling out the use of service personnel. A plan involving the use of 4,500 service drivers and 1,650 tipper lorries was considered capable of moving 100 kilotonnes a day of coal to the power stations.

A separate contingency plan, codenamed Operation Halberd, to use troops in the event of a dock strike, had also been drawn up.

The files show that there were two moments during the government’s bitter year-long struggle with the miners when Thatcher and her ministers “stared into the abyss” and glimpsed the possibility of defeat.

The first came in July 1984, when Britain’s dockers joined the miners on strike. The Downing Street papers show that Norman Tebbit, then Thatcher’s employment secretary, wrote her a “secret and personal” letter warning that “I do not see that time is on our side”.

In the face of secret estimates that they would run out of coal stocks by mid-January, Tebbit suggested urgent measures be taken, including opening a new front against the rail unions, to win the strike by October.

“In practice, we could not go right up to the brink,” he told her. “I am much concerned that the NUR and Aslef [the rail unions]which are so reducing the transport of coal and coke to the power stations are being carried out at very little cost to the unions, and at no cost to the individuals taking this action,” said Tebbit urging legal injunctions be taken out against them.

The second moment came that October when the combination of doubts about power station stocks and a strike ballot by Nacods, the pit deputies’ union, threatened a total shutdown in British coal production.

The secret list of “worst case” options outlined to Thatcher by Whitehall’s most senior officials included power cuts and even putting British industry on a “three-day week” – a phrase that evoked memories of Edward Heath’s humiliating 1974 defeat by the miners that brought down his government and which must have sent a chill down Thatcher’s spine when she read it.

The Cabinet papers also reflect the violence of the dispute that saw its bloodiest battle between police and flying pickets at Orgreave coking plant in South Yorkshire in June 1984. They show that in August 1984, the Association of Chief Police Officers told the prime minister that the miners, “frustrated by the failure of mass picketing, are taking to ‘guerrilla warfare’, based on intimidation of individuals and companies”.

They also show that senior Home Office officials shared the popular picket-line view of the Metropolitan police. The Met units sent to the picket lines are described as having been “valued in violent confrontations” but more likely to increase tensions the rest of the time.

The Home Office also told Thatcher that the most notable development in police tactics during the strike – the policy of “stopping and turning back” busloads of flying pickets on the motorways – was not the “unmixed blessing” it had been officially seen as. Officials pointed out that while the police had to know where the pickets were heading to intercept them, once they had turned them back, they had no idea which other picket lines they had gone to join.

The Downing Street papers also provide further confirmation of the role of David Hart, a shadowy old-Etonian, charged with organising and funding the working miners’ anti-strike movement, and nicknamed the “Blue Pimpernel” in Tory circles. Thatcher’s personal diary lists at least three face-to-face meetings with him at Downing Street, and in October 1984 a note on the file shows that he had phoned her in alarm that the press had found out that he had direct access to her. He told her he was “infinitely deniable”.

The papers also show the widely publicised “return to work campaign” was in reality “no more than a trickle” during the first six months of the strike, with no more than 500 going back to the pits in July.

Thatcher’s own handwritten notes on “possible strategies for the coal and docks dispute” paper for the 18 July meeting of Misc 101, the special cabinet committee on coal that she chaired, outlines the details of the plans to use the army. It involved using 2,800 troops in 13 specialist teams that could be used to unload 1,000 tonnes a day at the docks, but would require a declaration of a state of emergency to ensure they had access to the port equipment, such as cranes, that they needed.

The “secret” paper for the meeting spelled out the dangers a week after the dockers had walked out: “The political and economic stake[s] are much higher for the government in the coal dispute than in the docks dispute. Priority should therefore be: end the dock strike as quickly as possible, so that the coal dispute can be played as long as possible,” advised Peter Gregson, head of the Cabinet Office civil contingencies unit.

The agriculture minister, Peggy Fenner, advised that Britain would not run short of food supplies within the next 10 days but panic buying could drastically alter that. There were however looming shortages likely of certain kinds of fruit and veg, bacon, oil and fats and hard wheat.

Gregson added: “Even if no problem over food and oil … serious disruption to industry will soon be felt and there will pressure on government to find a solution.” He reminded Thatcher that troops had not been used to break a dock strike since 1950 and could bring more severe picketing and law-and-order problems.

The prime minister asked the attorney general to advise on how far it was possible to use troops to unload the food imports under a state of emergency even though there was not an immediate threat to the “essentials of life”.

Minutes of the secret cabinet committee, Misc 101, reveal Thatcher and her closest ministers were unsure of what to do: “It was not clear how far a declaration of a state of emergency would be interpreted as a sign of determination by the government or a sign of weakness, nor to what extent to which it would increase docker support for the miners’ strike.”

The armed forces minister, John Stanley, reported that troops could actually be provided on “a considerably larger scale” than the 2,800 in the plan. His pledge was never tested though, for that weekend the dock strike that had paralysed 61 ports for 12 days crumbled and was called off. It was immediately followed by Tebbit’s secret plea for tougher action to bring a swift end to the strike.

But Thatcher met this wobble by calling in Sir Walter Marshall, the head of the Central Electricity Generating Board, who reassured her that the coal stocks were not in danger of running out and that the power stations could be kept going at least until November 1985.

The second “darkest moment” came in October 1984. Thatcher had to contemplate possible power cuts and a three-day week if the threatened strike by Nacods, the pit deputies’ union had gone ahead.

Everything was done to avert that prospect and when it was called off the relief in Downing Street was palpable: “The news was announced this afternoon and represents a massive blow to [Arthur] Scargill,” read the “secret and personal”‘ daily coal report for Wednesday 24 October.

The strike was to drag on to the following March but the struggle had long been lost by then.

Follow

Follow